At the end of the mid-season finale of Mad Men last spring, something interesting happened. Don Draper handed over the reins at a pitch meeting with a new client to Peggy Olson. Peggy’s made pitches on the show before, but this one was different. This was one Sterling Cooper & Partners had wanted Don to make—because he’s Don, because he’s a man (and for various other less than noble reasons). But at the last minute, Don told Peggy it had to be her.

He knew that with Bert Cooper's death, there was a chance he could be voted out of the company, thus making his pitch null and void. But more importantly, he knew that Peggy’s idea, her perspective on the product, was more valuable than his own.

And she nailed it.

This was a tremendous few minutes in the history of Mad Men, not only because it meant watching Don express some humility (a rare sight), but also because it meant seeing Peggy in a moment of triumph.

And I don’t know about you, but I can’t recall this ever happening to any other female character on this show.

In the second episode of the first season, Betty Draper finds herself suddenly unable to use her hands. It’s a reference to the all sorts of mysterious ailments that plagued real-life bored housewives in the early 1960s. After she accidentally beaches the family car on a neighbor’s front lawn, her doctor suggests she visit a psychiatrist. To which Don says, “I always thought people saw a psychiatrist when they were unhappy. But, I look at you…and this [gestures at the room]…and them [nods towards the children’s bedroom]…and that [affectionately strokes her cheek]. And I think, Are you unhappy?”

When viewers watched this seven years ago, it made sense that Betty might be so unhappy, knowing what we know now about Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, the “problem that has no name.” Today, we’re well aware that the concept of a woman’s place being only in the home was one that just couldn’t work out. We know that going the way she’s going, Betty, a college-educated woman, has no hope of finding what she desires in life. And Don can’t provide much assistance, as he himself asks aloud later in the same episode, during a creative meeting about Rite-Guard, “What do women want?” He doesn’t know any better than she does.

When viewers watched this seven years ago, it made sense that Betty might be so unhappy, knowing what we know now about Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, the “problem that has no name.” Today, we’re well aware that the concept of a woman’s place being only in the home was one that just couldn’t work out. We know that going the way she’s going, Betty, a college-educated woman, has no hope of finding what she desires in life. And Don can’t provide much assistance, as he himself asks aloud later in the same episode, during a creative meeting about Rite-Guard, “What do women want?” He doesn’t know any better than she does.

You’d think that by Mad Men’s final season, nine years later in TV time, we’d be at a place where the female characters’ voiceless struggle, their inability to find a purpose, would be a thing of the past. But no. In so many ways, we’re right back where we started.

The reason Peggy nailed the Burger Chef pitch was because she was able to tap into something Don couldn’t—the notion that it’s OK to have a family that isn’t nuclear. As a divorced dad—and soon to be experiencing divorce number two, most likely—Don doesn’t exactly have the white picket fence anymore. But the difference between him and Peggy is that as a man, he does not let his temporary aloneness define him. His career is the locus of his success. Peggy’s definition is more complicated. In season seven’s “The Strategy,” she and Don brainstorm about the Burger Chef pitch, and she confesses that she’s just turned 30. And even though career-wise, she’s at the top of her game, she breaks down because she is still unmarried, and asks Don, “What did I do wrong?”

After all the strides they’d made, out of the kitchen and into the workforce, how did women in this time period get to a question like that? And how do they today?

In an effort to unravel this, I looked at what these female characters would have been reading in abundance at that time: magazines.

After all the strides they’d made, out of the kitchen and into the workforce, how did women in this time period get to a question like that? And how do they today?

In an effort to unravel this, I looked at what these female characters would have been reading in abundance at that time: magazines.

Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner has said time and again how much he hates heavy-handedness as a TV writer. So he sometimes skirts around major historical events, using them just to fuel character development (for example, Betty says she’s divorcing Don after the Kennedy assassination). But he often reflects lifestyle trends, fashion and consumerism in his story lines, and 1960s magazines are a great source of that. In a public interview at the Hearst building on March 19th, he told Town and Country Editor in Chief Jay Fielden, “Life magazine was very good. Anyone who ever wrote a word in the 1960s had one assignment in Life. We use it as a big source of research; I have them all over the set.”

Though I typically only compare the episodes of this show to 1969 issues of Good Housekeeping, this time I looked at a handful of the magazine titles Weiner and his staff use for inspiration—two issues per year from 1960 through 1969, the show’s duration. And because Mad Men is about advertising, I zeroed in on the ads. Then I compared those ads with the types of clients Sterling Cooper (and various iterations thereof) worked with through the show’s seven seasons.

What real-life ads would these characters have been noticing? What information would have been shaping their lives…and guiding their opinions? And most importantly, what kind of reading material might have been influencing this seemingly never-ending source of women’s distress?

Though I typically only compare the episodes of this show to 1969 issues of Good Housekeeping, this time I looked at a handful of the magazine titles Weiner and his staff use for inspiration—two issues per year from 1960 through 1969, the show’s duration. And because Mad Men is about advertising, I zeroed in on the ads. Then I compared those ads with the types of clients Sterling Cooper (and various iterations thereof) worked with through the show’s seven seasons.

What real-life ads would these characters have been noticing? What information would have been shaping their lives…and guiding their opinions? And most importantly, what kind of reading material might have been influencing this seemingly never-ending source of women’s distress?

Here’s what I found.

Ladies’ Home Journal

In the second episode of season one, when Don is still struggling to help Betty (or solve an advertising problem—you be the judge), he consults Roger Sterling. “What do women want?” he asks. And then a few beats later, “Who could not be happy with all this [points around the office, at the skyscrapers outside]?” And Roger replies, “Jesus, you know what they want? Everything. Especially if the other girls have it. Trust me, psychiatry is just this year’s candy-pink stove. It's just more happiness.”

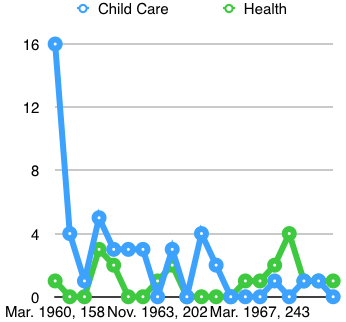

When I flipped through those first few 1960s issues of Ladies’ Home Journal (and I only looked at March and November, in an effort to remain neutral—March is often fashion-heavy, while November tends to have a lot of food ads; those numbers next to the issue dates are page counts), I was struck by the dominance of ads for food and domestic goods. But I’d suspected as much; when Betty Friedan pored over the previous 20 years of women’s magazines back in the early 1960s, she discovered a remarkable uptick in ads and articles revolving around the home. And this is, after all, a magazine with the word “home” in its title.

Domestic ads finally surpassed ads for food in 1968, which could be because women just weren't cooking at home as often by then (reflected on Mad Men via Peggy’s Burger Chef polls). The first fast-food ad I spotted was for Stuckey’s, in November 1967.

And the domestic ads in the late 1960s started bleeding into ads for other things—e.g., Palmolive is called a “dish manicure” (remember Madge?), and Ivory Liquid is touted for its “Young Hands Formula” (see left).

And the domestic ads in the late 1960s started bleeding into ads for other things—e.g., Palmolive is called a “dish manicure” (remember Madge?), and Ivory Liquid is touted for its “Young Hands Formula” (see left).

Across the board, every category related to a woman’s physical appearance increased in the decade, with beauty ads coming the closest to equaling the number of ads for food and domestic goods by 1968.

This was due to what Naomi Wolf describes in her 1990 best-seller, The Beauty Myth:

“In a chapter of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique entitled ‘The Sexual Sell,’ she traced how American housewives’ ‘lack of identity’ and ‘lack of purpose’…are manipulated into dollars. [Friedan] explored a marketing service, and found that, of the three categories of women, the Career Woman was ‘unhealthy’ from the advertisers’ point of view, and ‘that it would be to their advantage not to let this group get any larger….they are not the ideal type of customer. They are too critical!’

“The marketers’ reports described how to manipulate housewives into becoming insecure consumers of household products. ‘A transfer of guilt must be achieved,’ they said. ‘Capitalize…on ‘guilt over hidden dirt.’ Stress the ‘therapeutic value’ of baking, they suggested…they urged giving the housewife ‘a sense of achievement’ to compensate her for a task that was ‘endless’ and ‘time-consuming.’ Give her, they urged manufacturers, ‘specialized products for specialized tasks’; and ‘make housework a matter of knowledge and skill, rather than a matter of brawn and dull, unremitting effort.’ Identify your products with ‘spiritual rewards,’ an ‘almost religious feeling,’ an almost religious belief.’ For objects with ‘added psychological value,’ the report concluded, ‘the price itself hardly matters.’

“Modern advertisers are selling diet products and ‘specialized’ cosmetics and anti-aging creams rather than household goods…so modern women’s magazines now center on beauty work rather than housework: You can easily substitute in the above quotes from the 1950s all the appropriate modern counterparts from the beauty myth.”

Wolf says women’s magazines began losing readers in the mid-1960s when more women became “Career Women,” like Peggy, and were less and less interested in reading articles pertaining to housewives. So the magazines pursued them more aggressively using a new tactic: “Stripped of their old expertise, purpose, and advertising hook, the magazines invented—almost completely artificially—a new one. In a stunning move, an entire replacement culture was developed by naming a ‘problem’ where it had scarcely existed before, centering it on women’s natural state, and elevating it to the existential female dilemma.”

Female readers were by this time savvy enough to realize they were being manipulated. But despite the changing nature of the ads, women’s magazines were a highly important medium for them—so they couldn’t just stop reading cold turkey. The articles themselves, according to Wolf, “popularized feminist ideas more than any other” type of publication: “For a mass female culture that responds to historical change, [women’s magazines] are all that women have.”

They were putty in advertisers’ hands.

In the early 1960s, a good number of magic elixirs marketed in LHJ were health-related. They were usually ads for laxatives, hemorrhoid creams, dentures, toothpaste or aspirin. And there were a good number of child-care ads—but those plummeted early on (see above) and never quite recovered. Both categories were likely affected by the surplus of beauty and anti-aging advertisements.

In the late 1960s, LHJ just starts looking younger overall—the models are younger, and they’re often photographed next to children to emphasize their youthfulness. At-home hair color becomes much more prevalent—women who previously never would have considered such a thing were buying dye in droves. The word “feminine” suddenly becomes equivalent to the word “young,” which pops into nearly ever beauty ad. It’s even used to describe the vessels that hold their youth-inducing makeup (see above).

In the late 1960s, LHJ just starts looking younger overall—the models are younger, and they’re often photographed next to children to emphasize their youthfulness. At-home hair color becomes much more prevalent—women who previously never would have considered such a thing were buying dye in droves. The word “feminine” suddenly becomes equivalent to the word “young,” which pops into nearly ever beauty ad. It’s even used to describe the vessels that hold their youth-inducing makeup (see above).

LHJ started including more perfume ads in 1965, too—the same year they finally introduced a monthly finance column. So I guess the ladies could now find some way to budget for those pricy (and young) glass bottles.

Vogue

At first glance, it seems beauty ads went up only slightly towards the end of the decade in Vogue, but if you look at where they hovered (around 20 per issue) in the early 1960s, 50 ads per issue was a pretty big jump. Fashion ads would of course always stay high—it is the “fashion bible,” after all—but those dipped a bit, too, starting in 1968. And this was somewhat due to the effect of the sexual revolution, and how Vogue followed suit: “High-fashion culture ended, and the women’s magazines’ traditional expertise was suddenly irrelevant,” Naomi Wolf writes. “With the rebirth of the women’s movement, Vogue in 1969 offered up—hopefully, perhaps desperately—the Nude Look. Women’s sense of liberation from the older constraints of fashion was countered by a new and sinister relationship to their bodies…”

Nearly every beauty or fashion ad, often startlingly so, in the issues of Vogue from 1968 on was somehow also an ad for weight loss, anti-aging or sex (the last being so risqué that I can barely show them here). I’ve categorized them below and placed them in chronological order, to better illustrate the shift.

Beauty:

|

Revlon ad, early 1960s: “Dedicated to the woman

who spends a lifetime living up to her potential.” |

|

Yardley, early 1960s: “He never kisses you and

he never tells you he loves you?

Don’t brood about it. Take some direct

action, instead.” |

|

Germaine Monteil, late 1960s: “The whole—

a beguiling, man-oriented,

petal-y look you could eat with a spoon.”

|

Anti-aging:

|

Age-Wise Cosmetics, mid-1960s: “Helps older women,

too, but not as spectacularly.” |

|

Paradox by DuBarry, late 1960s:

“Young, beautiful and getting older.” |

|

| Elizabeth Arden, late 1960s: "21 today... 30 tomorrow. Face up to time flying." |

Weight loss:

|

Relax-A-Cizor, late 1960s: “I’m for smaller hips…

and…a Relax-A-Cizor in every home!”

(Yes, this is the product Peggy

tests in season one.) |

|

Warner’s, late 1960s: “Suddenly you look inches younger—

‘Inches’ by Warner’s shapes you the way your own muscles would if they could.” |

Sex:

|

| Liquessence by Dorothy Gray, late 1960s: "Its exclusive, antique penetrating moisturizer gives your lips youthful loveliness always." |

|

| Caress, late 1960s: "A new face for your legs." |

A strange fascination with wigs developed mid-1960s, too—here’s the approach advertisers took in Vogue, both early on and near the end of the decade:

|

Fashion Tress Inc., mid-1960s:

“Are you in love enough for a wig?” |

|

Reid-Meredith, late 1960s:

“The only thing she’s wearing is what we’re selling." |

And cosmetics became such a hot commodity that other brands started using the word “makeup” in their product names or copy, just so they could be associated with it:

|

Cantrece (from DuPont), late 1960s:

“A new kind of stocking that fits your

leg like make-up fits your face.”

|

|

Martex, late 1960s: “The made-up colors.

Martex makeup for your bath.”

(This is for towels. And you can’t

even buy this towel— it was made purely for the ad.) |

|

Shu-Mak-Up,

late 1960s: “Shu-Mak-Up changes any shoe shade as

easily as you’d change a

nail polish to accessorize a dress.” (Doubtful.) |

By 1965, Vogue models—who had once reclined serenely in their fur coats (nearly all the magazine’s fashion in the early ’60s was fur) in spread after spread—started running and jumping in their photo shoots, instead, repeating the pattern in LHJ: women meant to look childishly young (see right—that’s Vogue, not Seventeen).

And as the American woman broadened her horizons, car and travel ads proliferated. There’s only so much room in a magazine, though, which meant something else had to go—here, it seems it was child care and men’s care ads.

So for the first time ever, women were encouraged to invest the spare time and money once spent on their family’s well-being on their physical appearance, pleasure and new-found mobility instead. (Or, they were spending on themselves because fewer of them were wives or mothers.)

This is quite a change from the beginning of that decade. Debora L. Spar comments on this in her 2013 book Wonder Women: Sex, Power and the Quest for Perfection:

“The irony here is that the all-pervasive search for bodily perfection may come, in part, from the feminist movement. Because insofar as feminism liberated women to enjoy their sexuality, it also and simultaneously highlighted the importance of women’s physical and sexual attraction. Insofar as it prompted women to control their destinies, it also prodded them into controlling their bodies.

“The irony here is that the all-pervasive search for bodily perfection may come, in part, from the feminist movement. Because insofar as feminism liberated women to enjoy their sexuality, it also and simultaneously highlighted the importance of women’s physical and sexual attraction. Insofar as it prompted women to control their destinies, it also prodded them into controlling their bodies.

"And insofar as it told women to pursue their dreams, so, too, did it lure them into the perpetual pursuit of perfection. This wasn’t what the feminists meant, or even what they said. But as feminist ideas trickled through the ether of American society, they were translated into a vague credo of beauty as power, or at least an implicit belief that powerful women could, and therefore, should, still look great.”

And if you don’t believe the writers, makeup artist and costume designer on Mad Men have taken that credo to heart, just look at how the female characters have changed over the years:

Every one of them started out fresh-faced, and gradually got more glamorous by decade’s end. Not to mention that each has lost weight—especially Betty, after joining Weight Watchers (a 1960s invention) a few seasons back.

And then there’s Don:

Life

“Advertising is based on one thing: happiness. And you know what happiness is? Happiness is the smell of a new car. It’s freedom from fear. It’s a billboard on the side of the road that screams with reassurance that whatever you’re doing is okay. You are okay.” —Don Draper, season one of Mad Men

Flipping through the pages of the early 1960s issues of this weekly, it occurred to me what a voice box Don Draper truly is for Matthew Weiner. Because this is the magazine a man like Don would have read most fervently (we all know it wouldn’t have been Ad Age). It’s clear how much Weiner has drawn from Life, as its ads seem to most closely mirror the clients Don works with on the show.

In 1967, on both charts, the number of car ads spikes. Alcohol ads follow almost the same pattern in each, and the same goes for cigarettes. In the early 1960s issues, Lucky Strike was king. There were ads for hard liquor and Budweiser out the wazoo. It’s a whole different world than what you see in the women’s magazines. Also, ketchup was a very controversial condiment for a few years there—at least until Heinz won the battle of the brands (as it does on Mad Men, too).

The number of ads for food and domestic goods spiked and then dropped in real-life 1960s Life magazines; the same thing happens when you look at the clients in those categories on the show:

The dominant categories, other than cars, cigarettes and alcohol, were life insurance and technology. And while there were some ads that involved personal hygiene, they were almost always for shaving creams, razors and Ace combs. In other words: this magazine was not selling things women would have been particularly interested in, especially not towards the end of the 1960s. “What do women want?” Don asks? To not have to buy deodorant for their husbands, apparently.

And as far as women’s weight-loss ads go, well, Life was promoting the opposite (see left).

Strangely, however, just as the beauty ads were increasing in women’s magazines, the men’s care ads decreased in newsweeklies like Life. Were they going au naturel?

Or were they just too interested in travel to notice?

And as far as women’s weight-loss ads go, well, Life was promoting the opposite (see left).

Strangely, however, just as the beauty ads were increasing in women’s magazines, the men’s care ads decreased in newsweeklies like Life. Were they going au naturel?

Or were they just too interested in travel to notice?

A huge source of ad revenue for Life, there were virtually no ads in LHJ or Vogue for life insurance or financial investments. But strangely, the issue published a week after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination included no life insurance ads at all, while its men’s care ads went through the roof.

There is no real jobs/work-related category for LHJ and Vogue, because there just weren’t any ads for things like typewriters or pens. And when there were ads for photography, they weren’t for high-tech cameras, like the ones you’d see in late 1960s Life. They were for the paper you’d print the photos on; for the photo frames.

The world of Life in the 1960s is one that season one Don Draper would have fit into perfectly. It’s a world where the office dynamics still looked like this, regardless of the year:

Roger, Don and Pete all stand in somber colors in the foreground. Joan and Peggy, in muted tones, stand further back in submissive poses, to match their submissive roles.

And even in the later part of the decade, Life’s ads wouldn’t really allow for a group of colleagues that now resembles this one (excluding Betty, of course):

In this promo shot, the women are in the foreground as much as the men (and even more so, when you consider Pete and all the creatives joking around in the way back). The strongest female characters stand out in bold reds—their former muted yellows and greens now show up on the mid-level men’s jackets. Instead of holding their formerly assertive, fierce businessmen stances, Don and Roger retire into chairs—their positions showing their age (Bert Cooper often sat in group photos like this). But Joan is sitting, too—as a partner, she no longer has to wait on anyone. And Betty—well the sheer fact that Betty even exists in this photo is a big step up from that shot from season one.

In a live interview at New York’s Lincoln Center on March 21st, Matthew Weiner told Chuck Klosterman that his show has been inspired by the trait of “malleability.” “It’s such a part of our American culture,” Weiner explained.

So a show that often reflects the magazines mostly men were reading has now let the influence of women’s publications gradually seep through. Don’t forget that Life magazine published its last weekly issue in 1972. Though it continued on as a monthly, it was only moderately successful, never regaining its once acclaim.

Ladies’ Home Journal lasted until just a few years ago, and in 1970, its editor-in-chief agreed to put more news-worthy, topical content in the magazine after feminists staged a sit-in in his office for 11 hours.

In Wonder Women, Debora L. Spar writes, “Feminism was meant to be about expanding women’s roles and choices; about giving them the freedom, for the first time in history, to participate with men as equals, and to use their minds and bodies and talents and energies as they desired. Yet somehow this expansive and revolutionary set of political goals has been squeezed—or hijacked or mistaken—into something much more narrow and personal. Rather than trying to change the world, women are obsessed too often with perfecting themselves. Rather than seizing the options and challenges that society presents them, they are focused on controlling what they think they can: their bodies, their children, their homes.”

But I suspect that the last few minutes of the series finale will find Peggy in a bar, much like Don at the start of the series—or better yet, a nail salon. She asks the manicurist, “What night cream do you use?” And then, “So I could never get you to use another kind?”

(Stay tuned for my traditional "Good Housekeeping:Throwback Thursday Edition" post later this week!)

No comments:

Post a Comment