"Oh Very Young" by Cat Stevens (1974)

Oh very young,

What will you leave us this time?

You're only dancing on this earth for a short while,

And though your dreams may toss and turn you now,

They will vanish away like your daddy's best jeans

Denim Blue fading up to the sky.

And though you want him to last forever

You know he never will

(You know he never will).

And the patches make the goodbye harder still.

Oh very young,

What will you leave us this time?

There'll never be a better chance to change your mind.

And if you want this world to see a better day,

Will you carry the words of love with you,

Will you ride the great white bird into heaven?

And though you want to last forever,

You know you never will

(You know you never will).

And the goodbye makes the journey harder still.

Oh very young,

What will you leave us this time?

You're only dancing on this earth for a short while.

Oh very young

What will you leave us this time?

On the very first episode of Mad Men, "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes," a nervous young Don Draper met with a research scientist just before meeting with Lucky Strike. He was desperately grasping for any tidbit he could get for a pitch. Because at that point, he had nothing.

The researcher told Don that everyone believed cigarettes were poisonous, and it was going to be difficult to convince them otherwise. She suggested they take a Freudian approach: Tell them that Americans all secretly have a "death wish," and would never abandon a habit that made them feel rebellious. Don told her he found her methods perverse, and chucked her research into his waste basket.

Cigarettes have been part of the conversation from the start on Mad Men; before his meeting with the researcher, Don asked a busboy why he smoked, and he said he'd started during the war, when the government gave him a free carton a week. Don has been with or against Big Tobacco throughout, depending on what was most convenient at the time—he won over Lucky Strike by distinguishing them from other brands ("It's toasted."); when Lee Garner Jr. took Lucky Strike's business away, he wrote a "Letter to Big Tobacco" in the New York Times, stating how relieved he was to no longer be associated with them; when the American Cancer Society came calling, thrilled with his "ad," he tried to concoct a PSA; and when he discovered Cutler might use his poor relationship with Big Tobacco as a way to get him fired, he crashed a meeting at the Algonquin and told Phillip Morris, "Just know, the man who wrote that letter was trying to save his business, not destroy yours. Like Lou, I have over 10 years of tobacco experience. Since my first day on Lucky Strike, the government was building a scaffold for your whole industry. And I found a way to stay that execution in '60, '62, '64 and '65. I'm also the only cigarette man who sat down with the opposition. They shared their strategy with me, and I know how to beat it. I just keep thinking what your friends at American Tobacco would think if you made me apologize, forced me into your service. They are still your competition, aren't they?"

Cigarettes have been part of the conversation from the start on Mad Men; before his meeting with the researcher, Don asked a busboy why he smoked, and he said he'd started during the war, when the government gave him a free carton a week. Don has been with or against Big Tobacco throughout, depending on what was most convenient at the time—he won over Lucky Strike by distinguishing them from other brands ("It's toasted."); when Lee Garner Jr. took Lucky Strike's business away, he wrote a "Letter to Big Tobacco" in the New York Times, stating how relieved he was to no longer be associated with them; when the American Cancer Society came calling, thrilled with his "ad," he tried to concoct a PSA; and when he discovered Cutler might use his poor relationship with Big Tobacco as a way to get him fired, he crashed a meeting at the Algonquin and told Phillip Morris, "Just know, the man who wrote that letter was trying to save his business, not destroy yours. Like Lou, I have over 10 years of tobacco experience. Since my first day on Lucky Strike, the government was building a scaffold for your whole industry. And I found a way to stay that execution in '60, '62, '64 and '65. I'm also the only cigarette man who sat down with the opposition. They shared their strategy with me, and I know how to beat it. I just keep thinking what your friends at American Tobacco would think if you made me apologize, forced me into your service. They are still your competition, aren't they?" Mad Men is a show about the pleasures of consumption, and when he worked in advertising, it was Don's job to encourage people to believe that buying something could give them the feeling of "being OK." Even if that thing might eventually kill them. He wasn't supposed to care one way or the other.

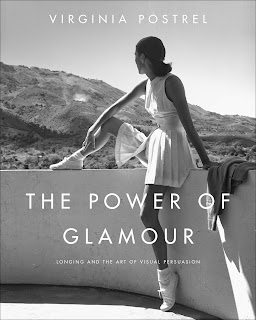

Betty is a prime example of Don's consumers, so of course she would fall prey to the ad agencies' tactics. In her book The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion, Virginia Postrel explains:

"Smoking used to be glamorous, the cigarette an icon of sophistication, power, sex, art and, to the young, all the grand and mysterious privileges of adulthood.... Smoking gave the awkward something to do with their hands and the graceful an extension of their grace. Like a folding fan, a plume of cigarette smoke simultaneously concealed and called attention to the smoker. Depending on the smoker and the audience, it could represent any number of ideals and aspirations.... In Franklin Roosevelt's upturned holder, a cigarette spoke of optimism and progress. In the Marlboro Man's rugged hands, it represented masculine independence. James Dean's cigarette symbolized rebellion, Marlene Dietrich's was all about seduction and a Shanghai calendar girl's epitomized modern femininity."

So when viewers learned Betty Francis had lung cancer in Mad Men's Episode 7.13, "The Milk and Honey Route," most accepted it as a probable end for this character, one who has smoked just as much as if not more than all the others on this show. And who on this show has been a more glamorous smoker than Betty?

If you asked Sally Draper in October 1970 why her mother had lung cancer, she might not have made that immediate connection, though. And that's because in 1970, people like Don had been successful. As he told Phillip Morris, he'd "stayed the execution" four different times. Because of Don, general public opinion had not yet caught up with scientific evidence.

According to the history department of Stanford University, "lung cancer was once a very rare disease, so rare that doctors took special notice when confronted with a case, thinking it a once-in-a-lifetime oddity. Mechanization and mass marketing towards the end of the 19th century popularized the cigarette habit, however, causing a global lung cancer epidemic. Cigarettes were recognized as the cause of the epidemic in the 1940s and 1950s, with the confluence of studies from epidemiology, animal experiments, cellular pathology and chemical analytics. Cigarette manufacturers disputed this evidence, as part of an orchestrated conspiracy to salvage cigarette sales. Propagandizing the public proved successful, judging from secret tobacco industry measurements of the impact of denialist propaganda....

"In 1954, for example, George Gallup sampled a broad swath of the U.S. public to ask: ‘Do you think cigarette smoking is one of the causes of lung cancer, or not?’ Forty-one percent answered ‘yes,’ with the remainder answering either ‘no’ or ‘undecided.’ In 1960, in a poll organized by the American Cancer Society, only a third of all U.S. doctors agreed that cigarette smoking should be considered ‘a major cause of lung cancer.’ This same poll revealed that 43 percent of all American doctors were still smoking cigarettes on a regular basis, with occasional users accounting for another 5 percent. With half of all doctors smoking, it should come as no surprise that most Americans remained unconvinced of life-threatening harms from the habit....

|

| Good Housekeeping, October 1970 |

"Cigarette makers spent countless sums to deny and distract from the cigarette–cancer link, in some instances actually quantifying the impact of their denialist propaganda. In 1973, for example, the Tobacco Institute hired AHF-Basico Market Research Co. and Audience Studies, Inc., to measure the impact of its 1972 propaganda film, Smoking and Health: The Need to Know, shown to hundreds of thousands throughout the country, including high school students. Prior to screening, viewers were asked a series of questions about whether the Surgeon General ‘could be wrong about the dangers of smoking’; the same questions were then asked after the screening. Anne Duffin at the Tobacco Institute was happy to report that the film had reduced by 17.8 percent the number of people agreeing that ‘Cigarette smoking cause[s] lung cancer’ (from 74.9 percent to 57.1 percent). The film had also produced ‘significant shifts’ in attitudes favorable to the industry in other areas, including whether recent reports had ‘overemphasized the dangers of smoking.’"

"Cigarette makers spent countless sums to deny and distract from the cigarette–cancer link, in some instances actually quantifying the impact of their denialist propaganda. In 1973, for example, the Tobacco Institute hired AHF-Basico Market Research Co. and Audience Studies, Inc., to measure the impact of its 1972 propaganda film, Smoking and Health: The Need to Know, shown to hundreds of thousands throughout the country, including high school students. Prior to screening, viewers were asked a series of questions about whether the Surgeon General ‘could be wrong about the dangers of smoking’; the same questions were then asked after the screening. Anne Duffin at the Tobacco Institute was happy to report that the film had reduced by 17.8 percent the number of people agreeing that ‘Cigarette smoking cause[s] lung cancer’ (from 74.9 percent to 57.1 percent). The film had also produced ‘significant shifts’ in attitudes favorable to the industry in other areas, including whether recent reports had ‘overemphasized the dangers of smoking.’"

Though women's risk of getting lung cancer is still slightly lower than men's, the disease is now the deadliest form of cancer. In the United States, according to the American Cancer Society, it's responsible for more deaths than those from breast cancer, colon cancer and prostate cancer combined. The survival rate remains at 15 percent; this is largely due to the fact that, as in Betty's case, there are rarely any symptoms until it is in advanced stages.

And smoking is responsible for 85 percent of it.

And smoking is responsible for 85 percent of it.

Betty's dealt with a cancer scare before. In the season five opener, as Don was busy adjusting to turning 40 and the demands of having married a 26-year-old, Betty was experiencing a significant weight gain and facing mortality in her own way.

In "Tea Leaves," the lump on her thyroid turned out to be benign, but one of the first things she did when she learned something was wrong was call up Don. She needed him to tell her that everything would be OK. She spent the rest of the episode feeling sorry for herself and wondering if anyone would even miss her when she was gone. Don wondered what his kids would do without their mother—he seemed unprepared to raise them on his own.

In "Tea Leaves," the lump on her thyroid turned out to be benign, but one of the first things she did when she learned something was wrong was call up Don. She needed him to tell her that everything would be OK. She spent the rest of the episode feeling sorry for herself and wondering if anyone would even miss her when she was gone. Don wondered what his kids would do without their mother—he seemed unprepared to raise them on his own. In "The Milk and Honey Route," Betty's reaction was much more mature. I couldn't help but notice though, as the camera zoomed in on her profile while the doctor told Henry the news, how much she resembled a profile painting from the Renaissance, a time when wealthy female patrons were often painted from the side: "From 1440 [on], nearly all Florentine painted profile portraits depicting a single figure are of women," writes Patricia Simon in her article "Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture." "Painted by male artists for male patrons, these objects primarily addressed male viewers. Necessarily members of the ruling and wealthy class in patrician Florence, the patrons held restrictive notions of proper female behavior for women of their class. To be a woman in the world was to be the object of the male gaze: to 'appear in public' is 'to be looked upon,' wrote Giovanni Boccaccio. The Dominican nun Clare Gambacorta (d. 1419) wished to avoid such scrutiny and establish a convent 'beyond the gaze of men and free from worldly distractions.' The gaze, then a metaphor for worldliness and virility, made of Renaissance woman an object of public discourse, exposed to scrutiny and framed by parameters of propriety, display and 'impression management.' Put simply, why else paint a woman except as an object of display within male discourse?

In "The Milk and Honey Route," Betty's reaction was much more mature. I couldn't help but notice though, as the camera zoomed in on her profile while the doctor told Henry the news, how much she resembled a profile painting from the Renaissance, a time when wealthy female patrons were often painted from the side: "From 1440 [on], nearly all Florentine painted profile portraits depicting a single figure are of women," writes Patricia Simon in her article "Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture." "Painted by male artists for male patrons, these objects primarily addressed male viewers. Necessarily members of the ruling and wealthy class in patrician Florence, the patrons held restrictive notions of proper female behavior for women of their class. To be a woman in the world was to be the object of the male gaze: to 'appear in public' is 'to be looked upon,' wrote Giovanni Boccaccio. The Dominican nun Clare Gambacorta (d. 1419) wished to avoid such scrutiny and establish a convent 'beyond the gaze of men and free from worldly distractions.' The gaze, then a metaphor for worldliness and virility, made of Renaissance woman an object of public discourse, exposed to scrutiny and framed by parameters of propriety, display and 'impression management.' Put simply, why else paint a woman except as an object of display within male discourse?Elsewhere in Italy, especially in the northern courts, princesses were also restrained by rules of female decorum but were portrayed because they were noble, exceptional women. In mercantile Florence, however, that women who were not royal were recognized in portraiture at all appears puzzling, and I think can only be understood in terms of the visual or optic modes of what can be called a 'display culture.' By this I mean a culture where the outward display of honor, magnificence and wealth was vital to one's social prestige and definition, so that visual language was a crucial mode of discourse..."

A display culture. Yeah, that sounds like Mad Men.

These women were more identified by their possessions—their jewelry, their dress—than by their facial expressions. You were not meant to see their eyes, the windows to the soul, except from a side view—their gaze showed their obedience. And the way they were represented was meant to show off their husband's wealth, because they were an object that belonged to him. They were a trophy. And often, because of the lack of modern medicine, these women died young, in which case their husband had this portrait of them to remember their beauty forever. They would never age, never tarnish. They would always be this perfect representation of success.

It's all that Betty was ever really raised to be, and something she never wanted to lose, as she explained to Don in season one's "Babylon." As she and Don discussed "The Best of Everything," both the novel and film version, Betty expressed her dismay at the aging Joan Crawford: "To think, one of the great beauties, and there she is...so old. I'd just like to disappear at that point. It makes perfect sense."

By the end of the episode, Betty covers up her abrupt dismissal by Jim Hobart from her modeling job by pretending she was silly to want to work outside of the home. She says being in Manhattan all day was making it impossible to get a decent dinner on the table anyway. Don tells her, "Birdie, you know I don't care about making my dinner or taking in my shirts. You have a job. You're mother to those two little people, and you're better at it than anyone else in the world...at least in the top 500. I would have given anything to have had a mother like you. Beautiful and kind and filled with love, like an angel."

(Don was surely unaware of Betty's true merits as a mother, but that's beside the point...)

The next morning, Betty wears a very angelic-looking sheer white robe and serves the children breakfast as "You Are My Special Angel" plays on the radio. She plays with Sally's hair affectionately, beaming with pride. Sally gets irritated, of course, and complains that she's trying to eat.

When Betty discusses her diagnosis with Sally, she's wearing a similarly angelic white nightgown. And unlike during her cancer scare in season five, when she worried that her children would "never say a nice word about her again," Betty has a level of confidence now, which has come with maturity. She is relying on Sally to follow her instructions with her funeral because she knows Henry will be too upset to handle it.

When Betty discusses her diagnosis with Sally, she's wearing a similarly angelic white nightgown. And unlike during her cancer scare in season five, when she worried that her children would "never say a nice word about her again," Betty has a level of confidence now, which has come with maturity. She is relying on Sally to follow her instructions with her funeral because she knows Henry will be too upset to handle it. And later, when Sally opens the note prematurely, of course Betty's main concern is her appearance in the casket. But more importantly, she applauds Sally's individuality and chutzpah—she seems to know she's been more successful than her own mother in the way she's raised her, because Sally is her own person. She's not ever going to be someone's possession; she is going to have her own adventures in life.

And though Betty says to Henry when she goes off to class, "Why was I ever doing it?" just the fact that she'd pursued going back to school at all is going to provide a great role model for Sally. Because her mother had a brain and wanted to do something with her life other than please a man—even if that pursuit only lasted a few months. She got to see her mother experience fulfillment, and that is priceless.

It's something her father is still trying to find.

I'm not sure that anyone would have predicted that Don might up and leave it all behind on his first day at McCann, but that seems to be what he's doing. With every episode this half season, he's peeled off more layers of his persona, and this one was more of the same. It's interesting that this episode would be called "The Milk and Honey Route," because despite Don's materialization of his inner hobo this season, he's not quite on that famed road of plenty. He's on his way to it in this episode (the real-life Milk and Honey Route, coined that by hobos in the 1930s because it was so bountiful, mostly consisted of Route 89, which heads south from Utah; Don tells Sally he'll hop on that road on his way to the Grand Canyon), but he never gets there. Instead, one of his most important possessions breaks down and leaves him stranded in tiny Alva, Oklahoma, for six days. And in that time, while Don does experience kind treatment from his hosts, it's usually in exchange for some kind of service on his part and they're a bit skeptical of him.

I'm not sure that anyone would have predicted that Don might up and leave it all behind on his first day at McCann, but that seems to be what he's doing. With every episode this half season, he's peeled off more layers of his persona, and this one was more of the same. It's interesting that this episode would be called "The Milk and Honey Route," because despite Don's materialization of his inner hobo this season, he's not quite on that famed road of plenty. He's on his way to it in this episode (the real-life Milk and Honey Route, coined that by hobos in the 1930s because it was so bountiful, mostly consisted of Route 89, which heads south from Utah; Don tells Sally he'll hop on that road on his way to the Grand Canyon), but he never gets there. Instead, one of his most important possessions breaks down and leaves him stranded in tiny Alva, Oklahoma, for six days. And in that time, while Don does experience kind treatment from his hosts, it's usually in exchange for some kind of service on his part and they're a bit skeptical of him.Weiner's attempting to illustrate the difference between 1930s America and 1970s America with this. Because, as I've mentioned before, in season one's "The Hobo Code," despite telling their sudden house guest that she'd have to boil his clothes, Don's stepmother Abigail is kind and Christian to the man.

She reaches into their coin jar and hands him one, saying, "My mama always said, life is like a horseshoe: It's fat in the middle, open on both ends and hard all the way through." There is a concept of human decency here, of camaraderie. Our country hadn't yet experienced the financial boom of the 1950s, a surplus of consumption that would eventually greatly separate the haves and the have-nots.

|

| Good Housekeeping, October 1970 |

|

| Good Housekeeping, October 1970 |

And they are proud of living this way, and defensive about it. Don empathizes with Andy, the cleaning help at the hotel (though he really just cleans out everything he can), because he knows what it is to want to escape a small, boring, repressive town. He even tries to correct his grammar several times, hoping to have an impact on him. But this is a town that has been this way for so long that it feels threatened by the changes going on in the outside world. Hence the song in Don's dream, "Okie From Muskogee." That was an award-winning country song that year. And while one could say Don is just returning to whence he came, by visiting these small Midwestern towns, in reality, he can never go home again, and for more reasons than he expresses to Andy (because he'd changed his name and pretended he was dead). He can't go home again because that small-town America of the late 1940s no longer exists.

Even the Grand Canyon Don's trying to visit was in a decline by the mid 1970s. For most of the century, visiting National Parks had been an important part of being an American and had defined most people's childhoods. But it's hard to make a trip out to visit one during a financial crisis.

Another example of the static nature of towns like Alva, OK: The veterans Don meets talk about the wars they fought in like they'd just happened yesterday. Don lives in a world where you are supposed to just move on and embrace the new America. But here, everyone talks of yesteryear fondly and it's very difficult for anyone to move forward.

And yet somehow, Don finds a way to care about the effects of his actions in a place like this. In "The Milk and Honey Route," he keeps encountering situations that draw on his skills and prior knowledge in ways that are immediately useful to himself and to others—not just channeled into a means of growing bullshit, as his hallucination of his father Archibald tells him in season three's "Seven Twenty-Three":

Archibald: Look at you, up to your old tricks. You're a bum, you know that?

Don: No, I'm not.

Archibald: Conrad Hilton? You wouldn't expect him to be taken so easily.

Don: Shut up.

Archibald: You can't be tied down.

Don: That's right.

Archibald: Look at your hands. They're as soft as a woman's. What do you do? What do you make? You grow bullshit.

Archibald: Look at your hands. They're as soft as a woman's. What do you do? What do you make? You grow bullshit.And in "The Hobo Code," Bert Cooper rewarded him for his determination and selfishness:

Bert: Don, I am appreciative of your talents, and although that can't be measured, I have made an effort to quantify [hands him a check].

Don: Twenty-five hundred dollars? I uh...

Bert: Thank you. That's what you say. [Looks at Ayn Rand book] Have you read her? Rand, Atlas Shrugged. That's the one.

Don: Yes, yes it is.

Bert: See, I know you haven't read it. When you hit 40, you realize you've met or seen every kind of person there is. And I know what kind you are. Because I believe we are alike.

Don: I assume that's flattering.

Bert: By that I mean, you are a productive and reasonable man, and in the end, completely self-interested. It's strength. We are different. Unsentimental about all the people who depend on our hard work.

Don gets his hands dirty in "The Milk and Honey Route." First he's able to identify exactly what's wrong with his car (he used to sell cars for a living). Then, he fixes a typewriter with ease (night school). And soon after, he manages to fix a Coke machine (the account he was supposed to get at McCann but never did). He even uses his war experience for good here—he commiserates with his new friends. Instead of repressing his memories, a practice that often keeps him isolated from others, he shares them, and is set free.

It's unfortunate that the person he's pretended to be all these years prevents those friendships from blossoming. In this small town, they can't see the real Don—they see all that he represents: a wealthy liberal East Coast con man. He is like a walking advertisement, and these folks see right through it. He is the one "creating the lie," as Midge's friends told him in season one. So his generosity is immediately questioned. He knows that somewhere along the way, he's made a misstep, which is why he tells Andy, "Don't waste this," when he suddenly gives him his car.

Don's experience this season seems as though it would be unique to someone who's gone through all that he has—it's easy to think he's just reached a point where he's tired of maintaining a false face to the world. Or that the reason he ran from McCann was because, as his father told him, he "cant' be tied down." McCann represents all that's wrong with advertising, in Don's mind. Except by 1970, Don and other creative minds could no longer escape places like McCann. Much like he can never go home again to that quaint Midwestern town, he also can't move forward in his business quite the way he had been.

In the PBS program "The Real Mad Men and Women of Madison Avenue," retired ad execs explain what happened to advertising in the 1970s: By the end of the 1960s, when ad agencies went public, clients could see exactly what was going on inside the agencies. They started figuring out how much money the agencies were truly making, and so they started bidding down—the agencies often couldn't survive because of that, and had to accept being absorbed by larger places like McCann. The idealism and creativity of the 1960s made a dramatic shift to the bottom line. So, what happened to advertising was Wall Street. People who would be young, great copywriters became hedge fund guys instead. Randall Rothenberg, president and CEO of the Interactive Advertising Bureau, sums it up best: "Call me old-fashioned, but I still think Bill Bernbach and David Ogilvy had it right. There's nothing that works better than a great idea. The spark of genius, it's the beautiful image juxtaposed next to another beautiful image in ways that are just emotionally appealing to you. It's the five words that give you a sense that no five words ever have before."

Anyone would want to run from a business they've lost control of and know will never be the same again. Anyone would want to run from the effort it takes to maintain a false persona for 20 years. But Don has a third, even more pressing reason to run away from it all: He's 44 years old.

At midlife, many people find that what was once satisfactory and fulfilling no longer is. We've watched Don experience this for the entire half season. He spent the first half of season seven humbling himself and attempting to get back into the good graces of his colleagues. Now that he's earned back that respect, and some riches besides, he's unhappy.

The U-shaped curve. Abigail Whitman's horseshoe. It would be great if we could say Don's midlife crisis (a term not known until a doctor coined it in 1966) was foretold in season one, but I'm guessing this is something Matthew Weiner came up with for this season because it's what he's currently going through. He often puts his own life experience into story lines. And right now, he's on the verge of ending what may be the biggest success of his life. As Don says in "The Forecast," "And then what?"

For some reason, part of me wants this show to end with Don placing that Social Security card and engagement ring on the real Don Draper's gravestone, to put all of the lies to rest. It seems he'd finally be free to live his life as he wants if he were to do that. Of course, that can't really happen—he can't ever be Dick Whitman again. Because according to the United States government, that man is dead. He can, however, return to whence he came in a more metaphorical sense.

In the article "Initiatory Experience," Kenda-Ruth Kumpf writes, "A midlife crisis sufferer seeks to recapture the first experience of splendor and regresses mentally to that time and place, hoping for a do-over—a replay. It is necessary to return to the prior innocence, but to repeat the former mistakes is to follow the familiar path that led to his present midlife collapse. Once at the original place of innocence a person is yet changed and must choose a new path, applying the experiences and maturity earned and learned from his journey to this point. Regressing is a backwards movement, whereas returning is using the past as an experience to propel growth and forward movement. To re-turn is to turn again toward something, but unlike a regression, it is revolutionary. Midlife is a tumultuous experience for many—whether it is a crisis or not. Revolution itself is turmoil. But accepting revolution is the first step to proceeding through it."

This is the reason why I believe Don may come back to his old life renewed from his travels, and will take on new adventures in a different way than before. He will be able to be "tied down" without feeling threatened by it, he can take care of his children in Betty's absence if he has to. Because, as even a TV show tells him in "The Milk and Honey Route," "family is everything."

This is the ending that would seemingly provide the most growth for this character.

If you look at all the other characters on this show, Weiner has provided them with the opposite outcomes of what you would have expected in this final season:

Ted Chaough was once a competitive go-getter, always at Don's heels. And then he was tormented by balancing a passion for Peggy with his need for stability within his family. Now, in this last season, he's landed a rather corporate position, and he's quite happy about it. He's grown to realize that he does better when he doesn't have to experience the stress of running a business, and he's OK with that. And after a half season of chasing mini skirts, he's found love with a woman his age who's "kind of deep."

Joan has stood up for herself (and all women) this season in a way she never would have in season one. Granted, she was tough, to the point where even Don was intimidated by her, but she accepted her gender role and used her feminine wiles to get ahead. Now, in this final season, she's found love on her own terms and seems to expect that she and Richard treat each other as equals. And though she couldn't stay on at McCann, she's been rewarded for her hard work and will be monetarily secure for the rest of her days.

And that explains why the woman who jumps out of a cake at the veterans' fund-raiser is dressed like this:

And why Don spills some of his secrets soon after.

"The Milk and Honey Route" was directed and written by Matthew Weiner, so it's no coincidence that so many literary references pop up within it. For example, Don reads The Godfather in the hotel, a story about the death of an "old Don." And in the end, the new Don moves out West.

At the pool, Don encounters a bathing beauty reading The Woman of Rome, a 1947 novel in which an idealistic intellectual betrays his colleagues (for reasons he cannot understand) and becomes disillusioned. In The Andromeda Strain, only two characters are spared complete annihilation, and that's a baby and an old man (the two ends of the horseshoe). The book is about a series of mistakes made by scientists trying to stop an oncological epidemic, only to watch the strain transform into something completely benign by the novel's end. It was one of the most compelling reads that year, because of the way it was written—Crichton used a nonfiction style, so everyone believed the fiction they were reading was truly happening.

Hmm. Sounds like a show I know.

Weiner has said on multiple occasions that one of his main inspirations for Mad Men was the work of John Cheever, most specifically a short story called "The Swimmer." In this story, a man who is so into his own image and prowess decides to up and swim across the county, via pool-hopping through his neighbors' backyards. But something goes terribly wrong in his swim—in a sci-fi twist, time speeds up...his strokes become more labored, he notices physical changes in his body, the seasons seem to change. And his neighbors, friendly and eager in the beginning of the tale, make comments about his family that bewilder him. By the time the man finally reaches home, his house is empty. He's lost everything.

As optimistic as I'd like to be about the ending of Mad Men, I sense this is going to most closely resemble what becomes of Don. As much as I would love to see him come home, take his children in and see Sally off to Spain, I think the odds are higher that we will see him continue to strip away the layers of Don, until he is finally living a completely authentic life.

Or until perhaps he's left naked, with nothing to his name, and steps back into the Pacific Ocean, as he did in season four, this time swimming out until he can swim no more.

Does Don find Jesus in the end? Maybe. Of course, in the New Testament, Jesus says, "If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me."

In every opening of every episode of this series, Don falls out of an urban skyscraper, eventually landing in his suit and tie on a couch, with one arm stretched out, facing away from the viewer.

In the end of "The Milk and Honey Route," he sits on a bench in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by green farmland for miles. He has no suit, he doesn't even have any luggage. He is facing us instead of facing away. And he is smiling.

If Weiner continues with opposite outcomes for each character, it's hard to find a better ending than that for Don. Of course he'd find happiness in the freedom to be himself. I think in this finale, that is ultimately what we are going to see, no matter what form it takes.

Until next week, "Don't waste this."

"The Times, They Are A'Changin'," by Bob Dylan (1964)

Come gather 'round people

Wherever you roam,

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown.

And accept it that soon

You'll be drenched to the bone,

If your time to you

Is worth savin'.

Then you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone,

For the times they are a-changin'.

Wherever you roam,

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown.

And accept it that soon

You'll be drenched to the bone,

If your time to you

Is worth savin'.

Then you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone,

For the times they are a-changin'.

Come writers and critics,

Who prophesize with your pen,

And keep your eyes wide,

The chance won't come again.

And don't speak too soon,

For the wheel's still in spin,

And there's no tellin' who

That it's namin'.

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin'.

Who prophesize with your pen,

And keep your eyes wide,

The chance won't come again.

And don't speak too soon,

For the wheel's still in spin,

And there's no tellin' who

That it's namin'.

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin'.

Come senators, congressmen,

Please heed the call.

Don't stand in the doorway,

Don't block up the hall.

For he that gets hurt

Will be he who has stalled.

There's a battle outside ragin'.

It'll soon shake your windows

And rattle your walls,

For the times they are a-changin'.

Please heed the call.

Don't stand in the doorway,

Don't block up the hall.

For he that gets hurt

Will be he who has stalled.

There's a battle outside ragin'.

It'll soon shake your windows

And rattle your walls,

For the times they are a-changin'.

Come mothers and fathers,

Throughout the land.

And don't criticize

What you can't understand.

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command,

Your old road is rapidly agin'.

Please get out of the new one

If you can't lend your hand.

For the times they are a-changin'.

Throughout the land.

And don't criticize

What you can't understand.

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command,

Your old road is rapidly agin'.

Please get out of the new one

If you can't lend your hand.

For the times they are a-changin'.

The line it is drawn,

The curse it is cast.

The slow one now

Will later be fast.

As the present now

Will later be past.

The order is rapidly fadin'.

And the first one now

Will later be last,

For the times they are a-changin'.

The curse it is cast.

The slow one now

Will later be fast.

As the present now

Will later be past.

The order is rapidly fadin'.

And the first one now

Will later be last,

For the times they are a-changin'.

.jpg)

3 comments:

Another outstanding analysis. Thank you.

Thanks! I know I didn't get the meditation or the Coke ad in there, but otherwise I think I got the ending scene right. I'll have my new recap up tomorrow!

Are you paying more than $5 per pack of cigs? I buy high quality cigs from Duty Free Depot and I'm saving over 50% from cigs.

Post a Comment